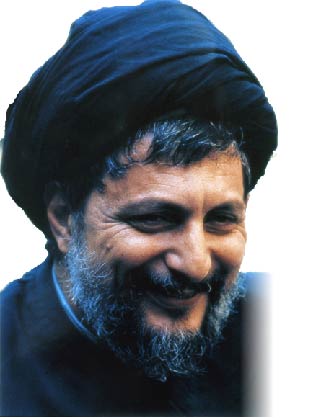

Last Friday, the Lebanese general prosecutor issued a warrant against Libyan President Moammar Kaddafi, a breakthrough in the investigation into the 1978 disappearance of Imam Moussa Sadr, who, in 1974, founded the Movement of the Deprived, the political wing of what would become the Amal Movement. Libya has always denied responsibility for Sadr’s disappearance, even though Sadr and his two travelling companions went missing on a trip there. No other suspects have officially been named, but the finger of suspicion has also been pointed at both Syria and Iran, although there is virtually no evidence to substantiate these claims.

The announcement came three days after Minister of State for Administrative Reform Ibrahim Shamseddine called for greater urgency in bringing the case before the International Court of Justice in The Hague. Shamseddine’s initiative, which has the backing of Justice Minister Ibrahim Najjar, who agreed to open a new file on Sadr, appears to have fallen on deaf ears within opposition ranks in the cabinet, while March 8-friendly media have accused Shamseddine, who confirmed that he will be running in the 2009 legislative elections, of electioneering on the back of the Sadr cause.

The criticism defines the battle for the moral high ground – combined with a parallel smear campaign – waged primarily by the March 8 bloc, whereby Hezbollah\'s undertakings to free Lebanese prisoners in Israeli custody, its continued search for information on the four Iranian diplomats kidnapped in 1982, and even its own call for answers to Sadr’s disappearance are considered heroic, even divine, while Shamseddine’s proposal is branded as mere opportunism, despite the judicial breakthrough.

A step forward

This is not the first time the Shamseddine family has championed the Sadr cause. His late father, Higher Shia Council President Mohammed Mehdi Shamseddine, embraced Sadr’s view of the Lebanese Shia being both Lebanese and Arab, and not a component of Wilayat al-Faqih, the Iranian Guardianship of the Jurist, as espoused by Hezbollah.

In November 2000, Ibrahim Shamseddine demanded that the Lebanese government present the missing imam’s case to the International Court of Justice at The Hague, while in 2006 and 2007 he made further calls to prioritize the case. Speaking to NOW Lebanon, Shamseddine said that for 30 years, no concrete or useful progress had been made in the case, and that when a minister makes this request, it should be welcomed and encouraged by all Lebanese.

“I appreciate the minister of justice’s appeal to launch a legal study, but I was expecting more encouragement from certain parties,” he said, adding that the Sadr case requires extra pressure, as the Lebanese judicial system has demonstrated certain limitations over the past 30 years.

“Of course, calling for bringing the case in front of the ICJ does not mean that it will happen; Libya has to approve, and I don’t think it will. However, we cannot sit back and do nothing. We need to bring attention to the case,” Shamseddine said. “We have to try, and it is the Lebanese government’s responsibility to take effective measures.”

His efforts may now be paying off. The recently published ministerial statement follows that “With regard to following up on the disappearance of Imam Moussa Sadr and his two companions, Sheikh Mohammad Yaacoub and journalist Abbas Badreddine in Libya, which is a major patriotic issue, the Lebanese government shall make strenuous efforts on all levels to reveal their fate, liberate them and punish those responsible for their kidnapping, as well as those who executed it and who are involved in it. The government emphasizes the need for the competent judicial authorities to do their job and take the measures stipulated by the Lebanese laws.”

Shamseddine said that the abovementioned paragraph scored two victories, namely including the words “Libya” and “liberate.” “For the first time, there is a mention of Libya being responsible for their disappearance, plus the fact that there is a demand to liberate them, not just close the files.

Last week’s warrant was a further breakthrough. “This is a significant development, but it is also necessary to fulfil the process,” said Chibli Mallat, a leading human rights advocate and lawyer for the Sadr family, talking to NOW Lebanon. Mallat added that it is a long process that requires the activation of the arrest warrants. “Nevertheless, the case has gained momentum after the new ministerial statement’s re-adoption and major amendments to the paragraph related to Sadr’s case.”

Meanwhile, Shamseddine is now keen to make the Sadr case a Lebanese, not a Shia, issue. “This is supposed to be a national cause,” he said. “If it’s not, let them tell us that it’s a Shia or a family affair, and then we will behave differently,” he said. “Today, I’m part of the government, and I came up with an initiative that is beneficial to every Lebanese, so what is it that has really annoyed [March 8]? It is clear [Libya] is being accused is, so what are they scared of?” he asked. “This is supposed to be an issue that concerns every Lebanese, and everyone should be cooperative.”

But party politics have once again contrived to muddy the waters. Pro-March 8 media have accused Shamseddine of using the Sadr case to puff up his election credentials, while at the same time to regain control of a cause considered to be their own. Al-Balad in particular vehemently declared that Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah was the only leader capable of getting results, using the bizarre logic he was the only one who has implemented Sadr principles of resistance.

Why not!

As Shamseddine’s initiative was being belittled, the Iranian Shura Council released a 300-page document dedicated to Sadr’s disappearance, which according to an article written by Mallat, published in late July in the Lebanese daily An-Nahar, provides the Sadr case with a boost on many levels, including a methodology on how to follow up the issue regionally and internationally.

Mallat said that this is an important step because this is the first time the Iranian parliament issues an official document regarding the Sadr case. “The Iranian parliament officially considers this a threat to the Iranian national security, as Sadr is a significant figure in modern Shia history, and his absence is a threat to the peace and well being of the Shia across the world, including the Iranians.”

However, Mallat stressed that although this document is noteworthy, it needs to be followed up and activated. “They have listed a number of mechanisms and practical steps to follow up the case, but we need to wait and see how they are planning to put it into action,” he continued.

As for Shamseddine’s call for bringing the case in front of the ICJ, Mallat believes that this step should be carefully considered. “Maybe this is not the best approach, as Libya can refuse the jurisdiction of the ICJ, which it can under the ICJ statutes. Therefore, it is best to activate the existing warrants through the judicial institutions in countries that might cooperate,” Mallat concluded.

Despite the attempts by some to politicize the case, the latest warrant, along with Shamseddine’s efforts, has given Sadr’s case an undeniable push. While the Hezbollah leadership has already tried to exploit Sadr’s good reputation to boost its popularity by drawing upon his call for “resistance,” the party has never drawn attention to the fact that Sadr called for a Lebanese, not Islamic, resistance, and was never a supporter of Wilayat al-Faqih.

His legacy is worth preserving.