* مؤتمر “كلمة سواء” العاشر "التنمية الانسانية ابعادها الدينية والاجتماعية والمعرفية"

The topic for this panel is Religious Perspectives on Human Development. My remarks could perhaps by characterized as something like Development Perspectives on Religion. "Development is a term of movement. To develop means to move from on place, the under- developed or less developed, to the more developed. So it is also a term of judgment. The language suggests that it is a movement from bad to good, or at least from less good to more good. How we understand those two places is extremely important and is determined by a great many assumptions about history, what it is and how it is told. So I will begin broadly with a book about how history is written that was published about five years ago by the Indian postcolonial theorist, Dipesh Chakrabarty called Provincializing Europe.

The "Europe" in Chakrabarty's title is not the landmass north of the Mediterranean, it is the political structures and that we have come to identify as modern the nation state, bureaucracy, and capitalist enterprise- structures that were never just European, and which now are global. He writes, it is impossible to think of anywhere go deep into the intellectual and even theological traditions of Europe. Chakrabarty means the way that histories of non – Western Nations are written as variations on a master narrative called 'the history of Europe'. History means a certain linearity of progress in which Europe is always the 'now' to the non Europe's not yet'. It is the modern to the traditional, the rational to the superstitutious. It is the developed in 'underdeveloped'. History consigns the non- Western world to what Chakrabarty calls 'the waiting room of history', and in doing so it converts history itself into a version of this waiting room. He doesn't means the waiting room of a doctor's office. He means the waiting room at a train station. The train is going one direction. Its path is determined by the steel rails on which it rides. 'We were all headed for the same destination' (8). The master narrative assumes that the trajectory of European history- the transition narratives which trace the development from feudalism to capitalism, from medieval to modern, despotic to constitutional, from underdeveloped to developed- can be mapped onto the history of say, Jordan or Lebanon or Iraq or India. Non- Western countries may have their own stories, but they are always subplots within the larger story. Within this larger story, the overriding themes are development, modernization and capitalism. Such histories are ones of absence and failure, lack and inadequacy. The failure to form a Western- style state, the inadequacy of the people to be democratic. Various historians place the blame in various places. For colonial historians the 'native' was the figure of lack, requiring a period of British or French education in order to be made ready for the end of history, citizenship and the nation- state. For the nationalist historians, the blame was shifted and the figure of lack became the peasant. In Jordan, for example, it is the Bedu who are this figure of lack. Or take the example of Iraq, Dexter Filkins, who has been reporting for the New York Times from Iraq since the invasion, wrote on Oct. 30 of this year, 'Two and half years later, its clear that a large percentage of Iraqis were either too traumatized or too tangled up in their traditions to grasp a democratic future'. The point is not to say whether this is true of Iraqis or not. Engaging in that argument would only make Chakrabarty's point, that this is the standard. That Iraqis can't be judged on their own merits, but only in term of how they measure up to their 'democratic future' with all that implies.

'Traditions' in the NYT quote may mean a lot of things. But one thing that it almost always means is 'religion'. We could read it as saying, 'A large percentage of Iraqis were too caught up in their religion to grasp a democratic future'. Essential to and inseparable from this master narrative of modern progress, is a deeply ingrained narrative of religious progress. Immanuel Kant, the greatest of the philosophers of the Western enlightment, wrote, "A historical faith attaches itself to pure religion as its vehicle, yet, if there is a consciousness that this faith is merely such and if, as the faith of a church, it carries a principle for continually coming closer to pure religious faith until finally we can dispense of that vehicle, the church in question can always be taken as the true one'.

When Kant says 'a historical faith' he means those particular sets of doctrines and practices we know as religions. When he says pure religion he means an individualist, inward experience of the heart. There are at least three claims being made in this one sentence. First, that there is one and only one 'pure religion' and it is tangled up with various expendable 'vehicles' called Judaism, Islam, Christianity, etc. Think of it like a cob of corn. The pure religion is the kernel obscured by the husks of doctrines, rituals, etc. Second, what counts as progress in religion is the gradual evolutionary shedding of the husk, getting down to the pure, undiluted religion. Third, the community that is closest to pure religious faith, closest to being able to dispense with the vehicle, is modern liberal Protestantism. (At least it was in the late 18th century when Kant was writing. Nowadays it is Secularism, the new religion of the West according to Pope Benedict XVI).

To get back to Chakrabarty's terms, anything less than Secularism is the 'lack' that must be filled, the 'incomplete' that must be completed'. Ranking the extent of the lack, the adequacy of the husks, became a task of 19th century anthropology. They spoke of higher and lower religions. The higher were the ones that most closely approximated what liberal Protestantism defined itself against, namely, Catholicism and Judaism and later Hinduism and Islam. The higher religions were those that most emphasized all those things as well as ritual, the saints, the priesthood. Here the case of Buddhism is very interesting. The Buddha comes to be understood as an Indian Martin Luther and Buddhism and Hindu Protestantism. But distinctions were also made within religions. The 19th century orientalists were enamored with Theravada Buddhism much more than with Mahayana Buddhism. Sufi Islam is so much more acceptable than Shi'a Islam. Sufis are 'mystical' while the Shi'a are religious with their veneration of Ali and Hussein and the rituals and iconography that brings with it. Take, for example, the popularity of Rumi in the West. This 13th century Sufi mystic was the best- selling poet in the US in the 1990s. but the millions who bought and read his poetry had no idea that for most of his life Rumi taught Sharia law at a Madrasa. And they couldn't care. His poetry, if not his theology, according to those American readers, sheds the husks of Islam and approaches pure religion. (That is, it does so if you don't know what you are looking for).

So far I have spoken of two grand narratives, two accounts of the waiting room of history, the political and the religious. But they are not two different narratives. They are aspects of the one narrative. How so? Both are essential to that hallmark of political liberalism, the separation of religion and state, Religion is always an object of fear. It is the thing which must be gotten out of the road of the march of progress. An example from Iraq will help to show how this works. A detailed thirty page proposal from UNOPS (United Nations office for Project Services) in May of 2004 called for a vast national democratic dialogue and spoke of inviting academics, journalists and NGO workers'.

There was not a word about religious leaders, and when I pushed the author of the proposal to account for this, she told me that religion is private'. She has a graduate degree from a very good American political science department). A certain account of religion is simply taken for granted by those with power in what gets called the 'international community'.

Such a claim is understandable in the West where it was invented and where, for many, religion often is as private as Kant wanted it to be. In Iraq it is just silly. The better argument, which I think the UNOPS claim is a cover for, is that religion in Iraq is public, way too public, and part of the point of spreading 'democracy' to it is to contain Islam by educating Muslims, especially the poor, uneducated, rural Muslims, to privatize their convictions.

But is that so bad? Isn't a secular state with only a minima; role for religion the best thing for Iraq? Well, I confess I think so. It seems obvious that the struggle for social justice requires something like these narratives. But then the question is, do I think that because it is true, or because, as an overeducated American, I lack the imagination necessary to escape the categories of political modernity? That, I think, is Chakrabarty's claim. His argument is not so much that the master narrative of Europe is 'bad' or 'wrong'. His point, rather, is to awake us to its enormous power. He is not offering us a good and right alternative to the bad and wrong. That is part of the point. If there were readily available alternatives then the narrative wouldn't be that powerful. A sign of its power is that its explanatory scope is so extensive that it cuts off the imagination before it even gets started.

What could it mean to expand our imaginations? Chakrabarty proposes that we begin by re-narrating those points of lack. He writes, "let us begin from where the transition narrative ends and read "plenitude" and "creativity" where this narrative has made us read "lack" and "inadequacy" (34-35). The problem, recall, is that it has become impossible to think without certain categories, Impossible to know if those categories are helpful or not unless we make the imaginative leap of thinking outside them. It is those categories themselves which force us to see 'modernity' as inevitable, that blind us to other modes of engaging the world. It is those categories that imprison the imagination instead of liberating it.

Can the aid agencies and development agencies help with that task? Can the international NGOs help with that task? The answer is by no means clear. The NGOs have come a long way in the last few decades. They have become, or tried to become, more sensitive to local populations. They have discovered things like appropriate technology and conflict resolution. They have tried to work more conversationally. They try not to assume that they are coming with the answers but instead are coming to discern answers in dialogue with local populations. Yet they seem to be under more criticism than ever before. A widely read recent text on globalization calls the NGOs 'the mendicant orders of global capital'. That is, they are to globalization what the wandering monks of the middle ages were to the Holy Roman Empire.

Can the local NGOs help with this task? Again, the answer is not entirely clear. In Iraq, unlike Lebanon or Palestine, the NGO is a very new thing, so MCC, some other international NGOs and UNDP did a lot of work to train local NGOs. We did this because we thought that Iraqi NGOs would do a much better job than we could because Iraq is their country, their people. And of course that is true. But what I quickly realized is just how much the NGO is a Western invention and therefore how much a UN workshop is training in how to become Western.

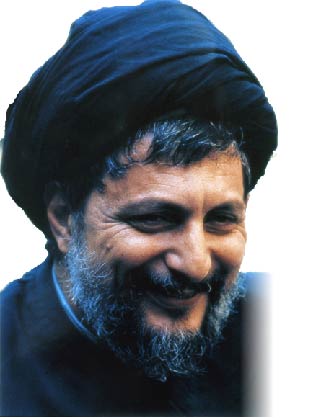

Can religious NGOs help with think tasks? I certainly hope so. Mennonite Central Committee works with the Imam Sadr Foundation for many reasons. One is that we think it does very good work. But another is that we want you to pry open our Western imaginations. But again, a general answer to this question is not entirely clear. To say why, let me give an example from the US context. Early in his first, term, George Bush announced a policy that he called support for 'faith- based initiatives'. That is, he proposed to increase the amount of money given to religious charities. The religious NGOs were very excited and lined up like panting dogs to get their share. MCC was one of the very few who refused because we have a policy against taking any money from the American government. But the question of whether to accept money from the US gov't was just one question. The other was, 'if the American empire likes what we are doing, shouldn't that suggest that we are doing something wrong?'

The lack of clarity in all these instances is due to a great extent to the closeness of the NGOs to the institutions of political power in our world. NGOs, aid agencies, development groups, always say the work for the poor. But if you look closely it can seem like they are just employees of governments, the UN, the institutions of global finance like the World Bank and IMF.

There is a story repeated twice in the Christian scriptures, in both the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Luke. It is of Jesus' temptation in the desert. Before the beginning of his ministry Jesus goes out into the wilderness. He fasted there for 40 days and nights and at the end of those forty days the devil came to him and led him up on a mountain and showed him all the kingdoms of the world. The devil said to Jesus, 'To you I will give their glory and all this authority; for it has been given over to me, and I give it to anyone I please'. And Jesus refused saying 'It is written, worship the Lord you God and serve him only'. Jesus could have been king. He would have been a better king than the Roman emperor. A better king than George Bush or Kofi Annan. He could have done a lot of good things. He would have cared for the poor and not just the rich. He would have helped the farmers and not just the business people. But he doesn't do it. He walks down off the mountain back into a life of poverty that ends in a bloody martyrdom. It is this direction that Christians are called to follow. But the history of the church, as I don't need to tell you, has been a history of refusing this example. It is a history, since Emperor Constantine in the 4th century, of priests holding hands with kings, of Christians taking up swords and guns, making crusades in the name of God or of country or of democracy, usually not knowing the difference.

But the true church, the repentant church, will always try to go the other way, away from power and kingship and towards the poor, what scripture calls 'the least of these'. But I don't think it is just a story for Christians. It is also a story for development agencies. Many of you here work for such agencies. And if you do you know that you are always forced to look in two directions. On one hand there are the poor and the oppressed that you want to help. On the other are the institutions of power from whom you get your money and to whom you must report. The place where our imaginations will be expanded will be with the poor, not with the powerful.

Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), 4 Italics in original. All further references will be noted parenthetically in the text.

Religion Within the Bounds of Mere Reason p. 122.

Kant again, 'we cannot expect to draw a universal history of the human race from religion on earth (in the strictest meaning of the word), for inasmuch as it is based on pure moral faith, religion is not a public condition, each human being ca become conscious of the advances which he has made in this faith only for himself. Hence, we can expect a universal historical account only of ecclesiastical faith, by comparing it, in its manifold and mutable forms, with the one, immutable, and pure religious faith. (p. 129).

Richard King, Orientalism and Religion: Postcolonial Theory, India and 'The Mystic East', (London: Routledge, 1999), p. 144-145.

Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000).